Jean-Luc Charles – 2A (Anciens Aérodromes) Member

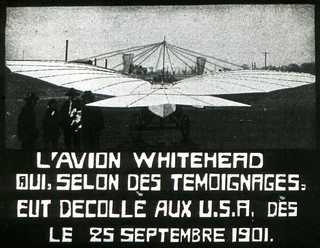

In our magazine #64 of December 2017, we presented you with the file of Alfred Carlier. It consists of a series of 5 films of still views on aeronautical topics.

The first image presented in the film on « Heroic Times » showed us an aeroplane, powered by engines with wings and empennages deployed like butterfly wings. The legend was as follows: « The Whitehead aircraft which, according to reports, took off in the United States on September 25, 1901. » (instead of Aug. 14, 1901). When you read the title, you immediately understand that there is much to discuss about this fact that is revolutionizing our historical data.

What was to happen happened through a man, Toni Giacoia, who devotes much of his research to Gustave Whitehead. As this very interesting story is not easy to tell, we (2A) preferred to let Toni speak:

« Open forum » by Toni Giacoia

Thank you Jean-Luc, but Gustave Whitehead was already known worldwide by Reader’s Digest in the 1940s, long before I became interested, and from a book published in 1937, by Stella Randolph. Whitehead had become increasingly world-famous from the period 1897-1904, when newspapers covered his many glider and flying machine inventions. It was mainly researchers Randolph and Maj. William J. O’Dwyer (AF, ret., dec.) who made important discoveries more than half a century ago. O’Dwyer and his daughter, Susan O’Dwyer Brinchman, never stopped looking since.

Strange as it may seem, Gustave Whitehead, who is now little known, is considered by some historians to be the greatest pioneer in aviation. It is probably no coincidence that the Information Service of the United States Embassy in Germany declared in 1983 that Gustave Whitehead was the rightful father of aviation. There are several reasons for this, including, among others, that Whitehead understood the stakes of the heavier-than-air flying machines; invented, built and successfully flew the world’s first powered aeroplane in 1901; designed and tested propellers; imagined and deemed to have tested steering in flight; and was probably at the top of what was done in aircraft engines. It is no coincidence that Octave Chanute praised his engines: his combination of engine, power, weight and fuel gave him a year’s lead over his competitors. Since the square of the velocity is the most important factor in the lift equation, this kind of asset could have a significant impact on the balance, in short.

It was in Bavaria that Gustav Weisskopf (Gustave Whitehead) was orphaned at the age of 13 in 1887 and then became an engine apprentice at Rudolf Diesel Werke where he learned about engines, fuels and cooling techniques. He left for the United States in 1893 after a stay in Brazil as a sailor. He tried kites in Boston where he worked for the Aeronautical Society (BAS). He built and tested gliders inspired by Lilienthal’s works. He then moved to New York, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and finally Connecticut. During this period, he believed in and designed a variety of powered, heavier-than-air flying machines (in addition to working as a night watchman !). He conducted many gliding flights and sometimes in public. He learned from his failures and there was a significant episode as early as 1899: a newspaper reported that Gustave Whitehead’s flying machine had hit the second floor of a building in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A police report was reportedly recorded. Several witnesses spoke of the accident where Whitehead and his passenger survived despite injuries to the passenger. Octave Chanute noticed Whitehead’s talent and suggested that the Wright brothers investigate the Bavarian’s lightweight engines in a letter to Orville Wright dated July 3, 1901. Some of his flights, powered or not, were reported in the press from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century. There is the famous powered flight of August 14, 1901, of Whitehead’s #21 aeroplane, based on the article of a journalist who was present during the flight. The flight was said to be for ½ mile and at a 50-foot elevation. Additional successful flights of that date were later testified in sworn affidavits by several witnesses. A number of newspaper reports and witness affidavits describe several more successful powered flights during the summer and fall of 1901. Other longer flights and flights in circuit, particularly around January 1902, suggest controlled flights, according to reports and the affidavit of his mechanic. A total of 12 local, newspaper reports of this era have been identified, crediting Whitehead with powered flights in 1901. Many articles credited him, worldwide, at the time.

How could such an inventor disappear from the newspapers for so long ? There are several possible explanations that I will not develop here. To put it in a nutshell, this is a very sensitive matter, as I have read. The situation is such that the State of Connecticut has officially recognized Whitehead’s flight history since the IHS institution Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft declared on March 9, 2013 that Gustave Whitehead had managed to complete long controlled flights before the Wright brothers. It was a major recognition from Jane’s, the world reference in this field. Pressure from pro-Wright groups, including the Smithsonian Institution, tried to reverse Jane’s previous stance. With great tact, Jane’s claimed that their editor had written his opinion, not binding on the institution’s stance even though Jane’s had published it. But, while recognizing the Wright brothers’ place as aviation pioneers, Jane’s still does not claim that the Wrights were the first to fly. As far as the other states and the United States federal government are concerned, they do not officially recognize Gustave Whitehead’s flights. The Wright brothers are recognized as the first to have flown, officially, except in Connecticut. However, IHS Jane’s does not seem willing to attribute the primacy of controlled flight to the Wright brothers. It is worth recalling that the first officially recognized flight was Santos-Dumont’s in 1906 and the first official circuit flight was Henry Farman’s in 1908 for they were validated by commissioners. Do we know the commissioners of the Wright brothers’ flights in 1903 and 1904 ?

I first contacted Susan O’Dwyer Brinchman, M. Ed. (Master of Education) who wrote Gustave Whitehead: First in Flight (2015). Susan is the daughter of deceased Major William J. O’Dwyer, a remarkable pilot instructor with the Army Air Corps and later the U.S. Air Force Reserve. He had spent half his life trying to solve the mystery of Whitehead’s flights. Maj. O’Dwyer also questioned the primacy of the Wright brothers’ flights. As he had a solid background in aeronautics, he could see that something was wrong with the official Wright version, whereas Whitehead’s hypothesis seemed much more likely to him particularly after he personally interviewed a number of surviving flight witnesses.

Shortly after I contacted Susan’s friend, a German, Karl Heigold, who very actively supports the Gustave Whitehead Museum and Research in Leutershausen, birthplace of Gustave Whitehead, 50 km west of Nuremberg. Karl Heigold is a member of the FFGW : the « Historical Flight Research Committee Gustav Weißkopf (Whitehead) » (HFRC-GW in English). William J. O’Dwyer was one of the founding members of the FFGW in 1973, along with Stella Randolph and Leutershausen’s Mayor Heinz Wellhöffer. I am very grateful to Karl for sending me Susan Brinchman’s book, Gustave Whitehead: First in Flight, which compiles a large number of elements to help me see this story more clearly. Similarly, I am very grateful to Susan O’Dwyer Brinchman, M. Ed. for the work she has done and all the information and images that Susan and also Karl have provided me with. Through interviews with eyewitnesses, research conducted by Stella Randolph, O’Dwyer and his Air Force Squadron members, and the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Society, as well as archives of numerous newspapers and letters, Susan and her father have accumulated about 50 testimonies and affidavits. Thanks to the work of William O’Dwyer, it was clearly demonstrated that the Smithsonian institution had an interest in the Flyer exhibition and even a contractual obligation not to recognize any flights prior to those of the Wrights’ of December 1903. It is now clear that this Contract is associated with support of Orville Wright versus that of Gustave Whitehead as “first in flight” despite years of Smithsonian claims to the contrary.

The Smithsonian, through the voices of past administrators; Tom D. Crouch, its current aeronautics curator; and Caroll F. Gray, a blogger-journalist defending the Wright cause (is that the role of a journalist ?) has been trying to deny it for many years, but time has done its work and the arguments now ring hollow. The fact is Smithsonian stands to lose the Wright Flyer as an exhibit if it recognizes Whitehead.

All these recent events have led to media coverage by CNN, CBS, Fox News, and The New York Times, to name a few. They all present the problem in a very honest and professional way because doubt is legitimately allowed. Only the Smithsonian groupies are left today to develop an argument against Gustave Whitehead, which remains embarrassing for the Smithsonian because proof of the contract with the Wrights’ heirs has indeed been established.

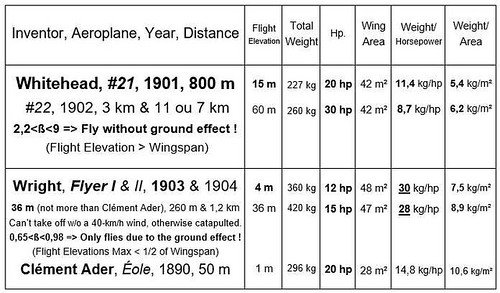

Regarding these elements only, Whitehead would be famous today. So much has been taught to Americans and then to countries around the world that the Wright brothers made the first flight, that some aviation historians even suggested that they have invented everything about aviation. The amateurs who bravely built the replica of the first Flyer certainly had no bad intentions, but they believed in this speech so much that they built a replica which never took off in front of President George W. Bush, right after his 100th anniversary speech commemorating the Wrights’ flights, on December 17, 2003. Ask a manufacturer of vintage aircraft: the first Flyers were not viable because they had anhedral wings, a factor of instability; they were too heavy; not powerful enough and unable to take off without a catapult, in still air, requiring a headwind of 25 mph on the beach at Kitty Hawk. They were like gliders on which obsolete engines were placed. It was the Frenchman Charles Marre (Bariquand & Marre engines) who would have insisted that Wilbur Wright finally decide to change engines at Le Mans. According to him, Wilbur was stubborn and it was thanks to an engine failure that he gave in to his advice. In your opinion, why did the Wright brothers never win the Deutsch-Archdeacon (1908) and London-Manchester (1910) ? Why did the Farman and Voisin brothers sell tens of thousands of airplanes for ten years when in the same period, the Wrights only sold a little over a hundred ? For those who still have doubts, look up in a video browser and type « Attempt to recreate Wright replica flight« … So ? Amazing, isn’t it ?

I argue a little differently in my book « Une autre histoire de l’aviation » because I have not mastered the chronology of this story as well as Susan O’Dwyer Brinchman, M. Ed. I am more interested in the airworthiness of Whitehead’s #21 and the Wright brothers’ Flyer. I will not detail here the many points that often plead for #21, nor will I go back over a very singular definition of flight reviewed and corrected by the Wrights. Just look at this table:

« Gustave Whitehead and his daughter next to the Condor or #21. Some aviation enthusiasts believe that Mr. Whitehead flew this plane on August 14, 1901, more than 2 years before the Wright brothers’ first flight. »

© Public domain, photo beach, aviation editoy Stanley Yale Br, Scientific American.

How could we not be surprised when the 2 replicas of #21 both easily flew – and one of these, at a 50 foot elevation and for ½ mile, just as Whitehead’s original #21 did, in Aug. 1901. The same cannot be said of the Flyer‘s replicas. We are not at the end of our surprises because our friend Charles Lautier keeps on researching in Connecticut and he has already found enough early, local news articles to reinforce our presumptions about Gustave Whitehead’s remarkable works. Charles Lautier, Susan Brinchman, M.Ed., Karl Heigold and I jointly share our thoughts and are always moving forward.

I knew Anciens Aérodromes (2A) by reputation before I came across Alfred Carlier’s films and I immediately guessed the silhouette of #21. I was puzzled – why September 25, 1901 instead of August 14 ? I reported this discovery to my American and German friends, and Susan immediately sensed a major discovery because she has a great memory of the events. Indeed, this date of September 25 could evoke a flight during the exhibition at the major fair in Atlantic City. Here is a lead that we had not imagined – the publications of the French Alfred Carlier ! If this information were to be confirmed, the research work on these films produced by 2A could have a significant impact on aviation history. Dear readers, if you hold Alfred Carlier’s archives and discover information about Gustave Whitehead, keep them in a safe place and contact 2A (Ancient Aerodromes) or Susan O’Dwyer Brinchman, M. Ed., at www.gustavewhitehead.info because within may be information of vital importance to aviation history.

The Australian John Brown played a major role in a very beautiful docu-drama entitled « Who Flew First ». It was written and directed by German-born Tilman Remme. Executive Producers were Brian Beaten and Celia Tait, both of Artemis Films of Fremantle, Western Australia. It is fair to say that John Brown has helped to make Gustave Whitehead known in Europe via Arte Channel in recent years but John Brown has never cited Susan Brinchman, M. Ed. in this film or in his publications, although she is essential on this subject. I find this unacceptable whatever the reason. On his website, John Brown has long persisted in mistaking a blurry picture of Montgomery’s glider as a Whitehead flight and has greatly discredited those who are seriously researching Gustave Whitehead. We do not find Brown citing the extensive work – ie more than 5 decades – of O’Dwyer et al and Brinchman. In addition, there are many unfortunate errors in the set of « facts » he has set forth in a recent book, and as a result, it reads more like historical fiction. Brown has still not removed the misinterpreted Montgomery’s photo that poses a problem and plays into the hands of the Smithsonian, since he is presented as a pilot and he has still not demonstrated in his work the airworthiness of #21 (although it is child’s play). That is why I recommend that you exercise extreme caution when consulting John Brown’s publications. For those who had doubts about what I am hinting at, here is a summary of the many inaccuracies and erroneous statements contained in his work:

http://gustavewhitehead.info/whitehead-historical-record-corrections/

I recommend the pages of these websites: http://historybycontract.org/, http://gustavewhitehead.info/ and https://www.weisskopf.de/ because they are the most reliable, as other sources often contain errors. Susan Brinchman, M. Ed., points out that Gustave Whitehead invented other flying machines, including a helicopter, that he considered #21 as a stage, and that he flew until 1915 according to witnesses.

I would like to thank 2A for the quality of their work. Their publications will certainly help me write the second edition of my book before a translation of that edition into English, within two years. I consider 2A‘s works to be of public interest because they search, find, and create materials that help those who are searching. For instance, Carlier’s film, by its date, could be a major discovery. 2A introduced me to the airfield of Ronchin (southeast of Lille) and its intense activity, with a meeting taking place a few days before Douai-Brayelle airshow, which I had previously described as a potential first meeting even before Reims airshow. Of course, Reims remains the first major international airshow, even if the Frankfurt and Vichy airshows had taken place a few days earlier. The fact remains that the first well-established airshow would have taken place at Port-Aviation in Juvisy (southwest of Paris) on a circular track with magnificent covered bleachers on May 23, 1909. (Further details in my book Une autre histoire de l’aviation, page 309).

- Toni GIACOIA Aviation English Instructor / Aeronautics Bachelor Tutor / BIA-CAEA Team / Author & Translator

https://fclanglais.fr ; https://airforces.fr

Auteur du livre « UNE AUTRE HISTOIRE DE L’AVIATION »